As I mentioned in the Alkmaar post , we spent 4 nights in Leiden over the Memorial Day weekend.

Our second full day there was spent making another side trip, this time to three UNESCO World Heritage Site locations. Although there are 10 UNESCO sites listed for the Netherlands as of this writing, only 9 of them are physically in the Netherlands. The 10th is on the Caribbean island of Curaçao. So, we were able to see 1/3 of the sites actually in the Netherlands in one day.

The first of these was the Ir.D.F. Woudagemaal or D.F. Wouda Steam Pumping Station. It’s located in Lemmer, about a 90-minute drive from Leiden.

It is a steam pumping station – the largest one in the world still in operation – that was opened in 1920 for the purpose of pumping water to prevent flooding. The station was designed by and later named after Dirk Frederik Wouda.

The Netherlands is a very flat country and therefore prone to flooding. The country is engaged in a constant battle to prevent this. There are over 1,500 pumping stations in the Netherlands, but most are now powered by electricity. The Wouda (pronounced wow-duh) station is unique because it’s powered by steam.

The function of the Wouda station is to pump excess water from the canals, lakes and ditches that make up storage basins into the IJsselmeer, an artificial lake that is the largest lake in Western Europe. (By the way, IJsselmeer is written correctly. The first two letters of the word are capitalized and are treated as a single letter in the Dutch language.) The station is capable of pumping 4 million liters of water per minute and can empty an Olympic-sized swimming pool in 35 seconds. Amazing.

There are two other pumping stations in the area that are put into use first when there is a danger of flooding, so the Wouda station is used only a few times a year. It takes 8 hours for the station to build up enough steam to begin pumping water.

A visit to the pumping station includes a stop in the visitor center followed by a guided tour.

Before the tour starts, you get to watch a 3D movie.

There’s Sean rockin’ his 3D glasses before the start of the movie. We were the only English-speakers on the tour, so they put on the English subtitles for us because the movie is in Dutch. It was a cheesy but entertaining little film. It’s a fictional story about a worker from the pumping station who is being thrown a birthday party at his home. Of course it’s pouring down rain the whole day so during his party he gets called into work to start up the machines to prevent flooding. I won’t give away the ending in case you ever want to go see it.

Because the tour was being conducted in Dutch, they gave us a little iPad so we could listen to the audio tour in English.

We later found out that you can download the free audio tour app in various languages on your Apple or Android device. Just look for the Woudagemaal Audiotour and pick the desired language. There are signs posted throughout the tour with numbers so you know which section to play on the app.

The smokestack you see there is 60 meters (about 196 feet) high. It is high enough so that local residents are not majorly affected when flue gasses are released from the smokestack. Construction on it was started in 1917 and was not an easy process. It was delayed both because of weather conditions including frost rain and winds and because of material shortages during World War I. It took about 10 months to complete and when construction could proceed, only 3 meters (just under 10 feet) or so per week were built. Finally, all that was left to do was place the lightning conductor on the smokestack and guess what? Yup, it was struck by lightning and collapsed and they had to start all over. As you can see it was eventually completed though.

Here is the actual pumping station.

The water in front of it is part of the storage basin mentioned earlier. The rounded arches at the bottom of the building are the water inlet tunnels where water from the storage basin is drawn into the pumping station. In front of the tunnels you can see what are called trash racks, and their purpose it to filter out debris such as leaves and twigs.

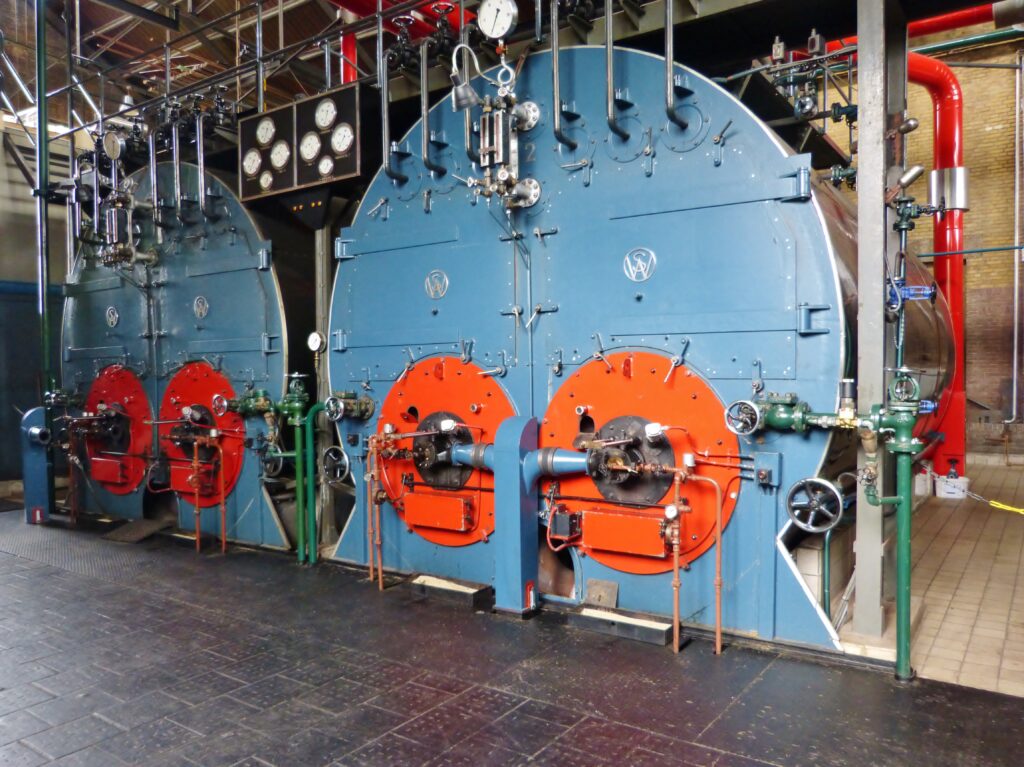

These are two of the four steam boilers in the boiler house.

These boilers actually generate the steam needed to run the pumping station. You can watch an animated film in the visitor center to see how the process works. Water in the boilers is heated with fuel oil. The steam produced is 185 degrees Celsius/365 degrees Fahrenheit. It then passes through a superheater where the temperature is raised to 320 degrees Celsius/608 degrees Fahrenheit.

The superheated steam is then used to run the steam engines you see here.

The large black wheel you see in the photo is called a flywheel and each of them weighs 10 tons. This part of the audio tour had a lot of technical terms like piston rods, cylinders, blah blahs, steam valves, cranks and more blah blahs. Obviously Sean was a lot more interested in that part than I was. It seriously sounded like blah blah to me, so I’ll move onto the next section.

These big, rounded, gray things that were described as looking like snail shells are called vane pumps.

There is a vacuum system on top of these pumps that suck water out of the storage basin. The water is then pushed out into the IJsselmeer by the centrifugal force that rotates the pumps.

Here you the condenser, which converts used steam back into water that is in turn reused in the steam boilers.

There was more blah blah going on here to describe the different pipes. As you can see, they are all different colors. This helps the engineers know what to work on when there’s a problem. As an example, the yellow pipes guides the steam back into the condenser and the light blue pipes are vent pipes. Again, Sean could probably tell you more about this than you ever wanted to know, so I’ll just continue on.

That was actually pretty much the end of the tour. Exiting the building, you see the Ijsselmeer where the excess water from the storage basins gets pumped.

Although the tour was conducted in Dutch, the guide did speak English and answered some questions we had. He was very enthusiastic about the tour and it turns out he doesn’t even work there. He is an engineer elsewhere and is just fascinated with the place so he volunteers there. It was nice to hear him talk about it because he was so into it. I joked about some of the blah blah technical stuff but overall the tour was really interesting and I’d recommend it.

Leaving the pumping station, we headed to the second UNESCO site of the day, which is called Schokland and Surrounding Areas.

This one took us a little while to figure out because it’s spread out. We ended up driving to different parts of it but there looked to be some nice bike paths between the locations as well.

The first place we ended up going to was the Geogarden. We weren’t even sure we were at the UNESCO site because this area is mainly a bunch of rocks. About 175,000 years ago, the land here was covered in ice. All kinds of rocks, some of them millions of years old, were carried here by the ice from Scandinavia and were left behind after the ice melted.

A lot of the information at the Geogarden appeared to be geared towards children and I was amused by this sign.

The English translation was “Dinnertime. They have caught a reindeer. From close up it is a huge animal! Onk’s father starts by making a sharp knife by striking a flint against another rock. Splinters fly in all directions. The adults then cut the reindeer open. Just look at all that blood.”

Sorry, I’m laughing just typing that because you would just never see either that drawing or that description on anything in the U.S. that was meant for children. You might traumatize them talking about where food really comes from.

Anyway, if you’re a geologist or just really into rocks you might enjoy this, but after we took a short stroll around one of the walking paths we were ready to move on.

The next part of the site that we stumbled across was the former harbor of Emmeloord.

Back in the Middle Ages, the land in this area was a swampy bog. The people in the area built three artificial “dwelling mounds” of which Emmeloord was one.

Storms and flooding caused large pieces of land to be torn from the swampy, boggy, area and eventually an island was formed as a result.

In order to prevent further erosion and flooding of the island, wooden palings (pieces of wood that make up a fence) like the ones you see here were put up.

The measure worked only temporarily, because in 1825 a storm flooded the island and ripped out the palings. Houses and buildings were destroyed and people were swept out to sea. Finally, in 1858, the king ordered the island to be evacuated because it was unsafe for human habitation.

From 1936 to 1942, the Zuiderzee – a bay of the North Sea – around the island was drained and Schokland then became surrounded by dry land instead of water. It is referred to as “island on the land” because the island is now surrounded by dry land instead of water.

At one time there was talk of leveling the island so the land could be used for agricultural purposes. That never happened, and instead Schokland was preserved and the Emmeloord harbor was reconstructed.

That’s a reconstruction of the light beacon that used to be at the harbor.

The Emmeloord area had signs along the walking path to explain how difficult life was on the island. The water surrounding the island actually came right up to people’s homes and buinesses. There were no sidewalks and the simple act of walking required Herculean effort.

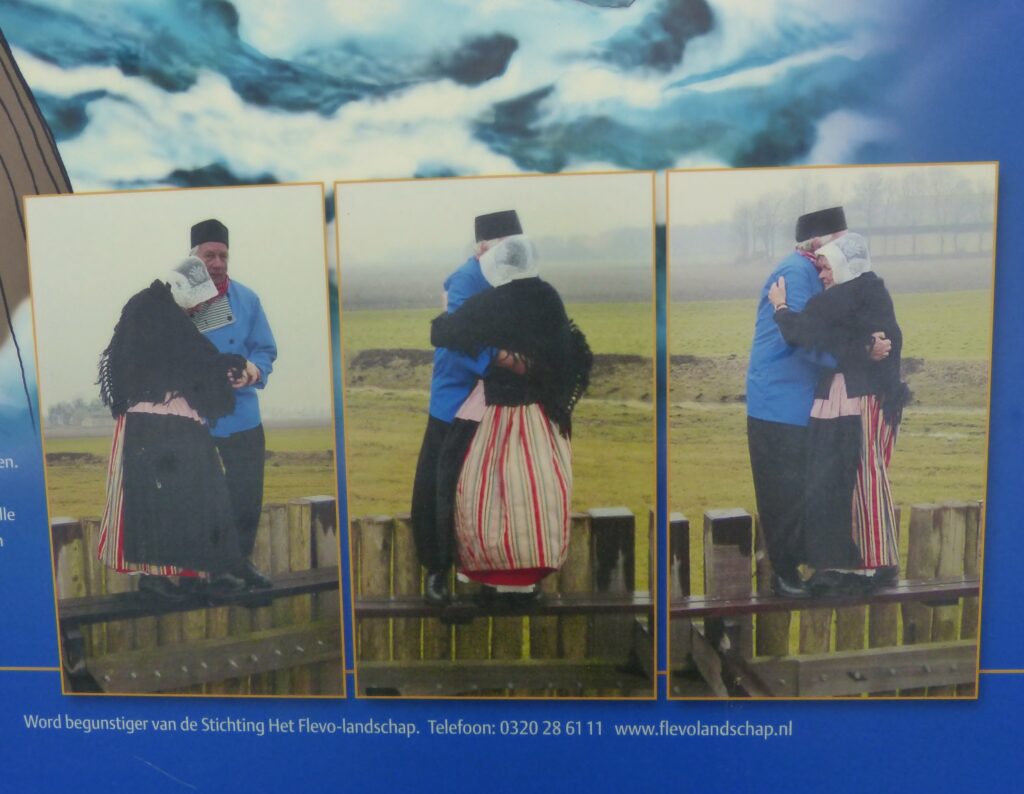

This sign illustrates what happened when two people were walking towards each other and had to do what was called the “Shokker dance”.

It didn’t say what happened if the people didn’t like each other. “Um, yeah, this big wave came along and, um, Jan was swept out to sea….”

In addition to walking being difficult, the islanders regularly experienced shortages of food, drinking water and fuel. The village was also subject to damage from ice floes.

After we walked around Emmeloord, we drove to the Zuidpunt (southern tip) of the island of Schockland.

One of the sights at the Zuidpunt is the remains of a fire beacon, used for sea navigation, that you see here.

The storm of 1825 that you read about earlier destroyed the first beacon, which was square and had an open fire for light. In its place a round, brick tower was built that had a coal fire for light. What you see above is the foundation of that round tower. An iron tower was later built on the same spot, but it was dismantled two years after the island became surrounded by dry land instead of water. (TIP: If you visit the site, look for signs that say Vuurplaat. The literal translation is “hot plate” and that’s where you’ll find the fire beacon.)

Near the fire beacon are the remains of the Church of Ens.

The oldest parts of this church date back to the year 1300 and it was in use until 1717.

If you’re interested in visiting Schokland and would like more information before you go, I recommend clicking here to check out their website at http://www.schokland.nl/pageid=23/EN.html.

Our last UNESCO site of the day was the Defence Line of Amsterdam (yes, Defence is spelled with a “c”).

The Defence Line consisted of 45 armed forts that were built between 1883 and 1920. They formed a ring around Amsterdam, about 15 km (9 miles) out from the city center in all directions. The entire line is about 135 km (84 miles) in length. The purpose of the forts was to control the water in the surrounding canals. In the event that Amsterdam was attacked, the city could defend itself by using the water to temporarily flood the land around the forts. The enemy would then be unable to get any closer. The use of the forts for defensive purposes was abandoned after World War I.

This is not an easy site to visit because many of the 45 forts are not open to the public for various reasons. For example, some are private property now and others are part of protected nature reserves. Other forts are open only a few days a month or a few days a year. Some can be visited only by making a written request for an appointment, and some require you to pay for a guided tour. Others are now businesses such as a wine importer, and you can visit the fort only when the business is open for wine tasting.

You can check out this map to get details on each fort. Just click on a blue pinpoint and then click on the word “details” in the box that pops up.

Also, if you’re driving around the Netherlands searching for any of the forts, look for signs that say Stelling van Amsterdam.

After much clicking around on that map to find a fort that was open during our visit, we decided on Fort Bij Aalsmeer.

It’s on the southwestern part of the ring near the town of Aalsmeer. There’s really not a heck of a lot to see at this fort as you can tell from the photo. There is a small museum at the fort called the Crash Museum, but it’s an air war museum related to World War II and has nothing to do with Defence Line.

So, that concluded our day of visiting UNESCO sites in the Netherlands. You can tell what a vital role water has played in the history of the country from these three sites.

Have you visited any of these sites? Tell us about it here or on our Facebook page!